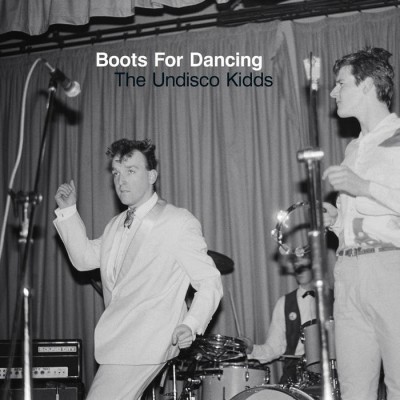

A retrospective Boots for Dancing collection may finally give the long lost funk-punk pioneers the recognition they deserve, writes Neil Cooper

November 28, 2015

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

It was a poet who gifted the name to Boots For Dancing, Edinburgh’s critically-neglected agit-funk auteurs led by vocalist ‘Dancing’ Dave Carson during the first post-punk flourishing of 1979-82. The phrase was introduced into the lexicon by way of an off-the-cuff counterpoint to another band’s three-word melding of socio-cultural tropes. These were forged in the heat of a generation’s existential disaffection in late 1970s Thatcher’s Britain. It also tapped into everything Boots For Dancing were about. Here was a name that implied a Doc Marten-buffed youth club gang cutting loose from the working week and letting off their collective tension on the floor. There was a sense of pride, too, in such a mass ritual, where sartorial elegance and cutting a dash was as much a part of the experience as the moves themselves. Looking good, feeling better was an unspoken mantra. It came with a package which understand music was a matter of life and death. It also democratised the dance-floor beyond the stages that separated performers from their audience and put the former on a pedestal just out of reach.

‘Twas ever thus with working class musical revolutions, from jumping Jive to Northern Soul to Acid House and beyond. Not the stuff of super-clubs and stadiums – something more intimate, born out of pub function rooms, dance halls and social clubs. These are the places and spaces where real pop art comes from, because the people making it or hearing it are living it, experiencing every second-hand emotion from the songs of strength and heartbreak that lift them onto the floor for real. Some might call it Soul.

But in the late 1970s, life on the streets of any British city or small town was tense, especially for teenagers spewed out of school into the dole queue, where one-time factory fodder were put into another form of production line, just as mechanically choreographed. To step out of line and to dare to be different was not the done thing.

So it was when Punk happened, as, beyond the tabloid outrage and short-lived explosion of Dada/Situationist-inspired nihilism, that community (who didn’t even know they were part of one yet) began to find their voice.

“There was a solid hardcore of Edinburgh punks,” Dave Carson remembers, “probably a couple of hundred, who went to different venues. There was a youth club basement in a church in the west end called the Cephas Cellar. It was probably quite a small scene with people from different housing estates and different schools discovering this emerging youth culture and it was really exciting.”

In Edinburgh, the catalyst was The Clash’s White Riot tour, which opened at the city’s Playhouse on May 7, 1977. The galvanising effect can’t be attributed to the headliners, who postured as well as any old pros, but to support acts The Slits and Subway Sect. Those bands’ mix of rudimentary musicianship, speak-easy bonhomie and sartorial ordinariness, as well as attitude aplenty, was far from the tabloid idea of ‘Punk’.

“It was very convenient that all these bands played on the same night,” says Carson, who was in attendance. “Very few people mention that the Jam played as well, but they were second from the top after the Buzzcocks, Subway Sect and the Slits, and you don’t see a line-up like that very often.”

Because of this, and contrary to popular mythology, Scotland’s rich and fecund music scene didn’t begin in Glasgow, where ‘punk’ gigs were then banned by the local council. Big Gold Dream: Scottish Post Punk and Infiltrating the Mainstream, is a lovingly-realised documentary film made in 2015 by Grant McPhee. As this extensive study of the era between 1977 and 1982 reveals, The Sound of Young Scotland began in a flat in Keir Street, next to Edinburgh College of Art on the cusp of the city’s Tollcross neighbourhood.

Here, co-conspirators Bob Last and Hilary Morrison would set down a blueprint for pop entryism via Fast Product and Pop Aural records, labels which focused on packaging as much as music. As records, the twelve releases on Fast were several works of art in one, with the sleeves wrapped around each disc as significant as what was on the record in a then punky but now commonplace form of packaging.

As for the music itself, in releasing the first records by The Mekons, Gang of Four, The Human League and the Dead Kennedys by way of Scars, Fire Engines and Boots For Dancing, Fast Product and Pop Aural would eventually go on to change the world. Until now, Boots For Dancing were the missing link in such a crucial seam of influence.

The Undisco Kidds by Boots For Dancing is available on Athens of the North Records: http://www.aotn.co/

The record can be heard here: