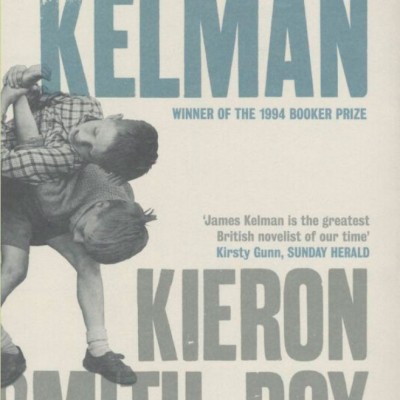

Which novel would you recommend to someone who had never read a word written in your country? The first stop on our tour is Scotland, where Alan Warner highlights James Kelman’s astonishing Kieron Smith, boy

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

If I could recommend just one book to a foreign reader and she had no knowledge of Scotland or of Scottish writing, I would tell her to carefully and slowly savour the novel Kieron Smith, boy by James Kelman, published in 2008.

It wouldn’t be the least challenging book for her to read compared to some of my favourite, old and trusted war horses of Scottish Literature. George Douglas Brown’s acid novel of 1901, The House with the Green Shutters, would alert her to a provincial tragedy – a merciless study of greed, youthful oversensitivity, Scottish small town malice and marriage turned pitiful; but what a cruel and ultimately vengeful book with which to welcome someone to a culture!

We hear a great deal about The Private Memoirs and Confessions of A Justified Sinner by James Hogg, (1824) – and rightly so. An astonishing, unfathomable thing, as great as Wuthering Heights, (both, like Kieron Smith, boy feature ‘non-standard’ English). Yet there is something European about Justified Sinner’s massive sensibility, and that long, strategic ballet of an opening before the book pivots round from view point to view point – it’s a modernist – nay, postmodernist novel, one hundred years ahead of its time and there is every reason to celebrate it; a confounding and endlessly fascinating introduction to Ecosse – but what a fiery baptism!

Kieron Smith, boy is the story of a life in motion, a young modern Scottish life, from the time when Kieron is at primary school up until he’s well into secondary. Kieron moves house, plays in backyards, explores countryside, moves school, goes to football, loses pals and makes them, grumbles at parents – it is an utterly unremarkable male Glasgow childhood. Yet the ‘story’ is rendered triumphant through the medium of the language alone which, before our very eyes, is prone to alchemical transformation – Kieron’s unfolding voice is in itself the dramatic idiom as it adapts and is buffeted by socialisation, by the enrichment of thought, by the growth of a proud recalcitrance. At this novel’s heart – as with all Kelman’s work – is an unfettered inner voice, a living consciousness in motion, pouring forth truth in all its undiluted generosity and continual inventiveness.

When I was younger, a word – a concept – was bandied about with frequent ease: ‘identity.’ Has identity become – perhaps momentarily – a troubling word, an embarrassing concept that doesn’t fit in to more embracing notions, such as rapacious global capitalism and uno mundo nonsense? I am sure you don’t see ‘identity’ and its pesky demands talked about quite so much these days. The concept of identity is often orbited by ideas of colonialism, or more accurately, of identities being deliberately – not inadvertently – suppressed by majority cultures. I hope I am mistaken in this, and I will be happy to be proven wrong, but I deeply fear for what we might choose to call: a Scottish identity; how much of it will actually survive in another seventy years? And yes, of course, Scottish identity is a protean thing, a multifaceted thing and we shouldn’t forget that. But a valid Scottish identity, a valid culture is also confirmed in all its richness within the novel Kieron Smith, boy and that should not be overlooked or denied. Because – believe me – some people do want to deny it and suppress it. This identity should be defended. In the onslaught of global English and indeed the globalised novel in English, our reader will have to work a little bit with Scottish reality here, but that is why I would commend this book to her with good heart.

Kieron Smith, boy is an overflowing repository of our living language, as spoken in Scottish childhood and in youth. Kelman has written Kieron’s complex first person voice – his living consciousness – as totally modest yet infinite, utterly unpretentious yet universal, simple yet profound. It’s also – a hell of a lot of the time – very, very funny and deeply touching:

“The wee shapes started moving about, then with their tails. That was the tadpoles. Ye gived them names then put them back down the field into the burn so they could swim about. Then they came frogs. When ye saw frogs down the field ye called their names so if they came to ye, well, that was them.”

Consider this extract. It’s funny, it’s perfectly observed, contains a whole geography, several movements in time and a reanimation of language. Look at that first sentence – what’s going on there? Kelman has effortlessly made Kieron skip a week or so – as tadpoles grow. It is not good global business English, oh no, it isn’t ‘correct,’ yet how achingly authentic to how we thought as kids; it contains the mythologies of our childhood and of all childhoods.

For four hundred pages, Kelman rolls out this language in a hallmarked lexicon of necessity and beauty to give us Kieron. This novel’s temporal setting is vague, perhaps in the early 60s, maybe even into the early 70s – entrenched sectarianism, rehousing – but so universal is the imperative viewpoint of childhood that we sense these upheavals at a tangent. Kelman gifts us the consciousness of childhood as an eternal experience. Gradually the language thickens, the complexities swirl, the swear words are not redacted – it is no longer: “he did a bl***y.” Instead the world is in a slightly darker and more complex mode; a sadder one as we climb through new orthographies which predict the loss of Kieron’s boyhood when walls to climb, jaggy nettles and huge boulders, (“Who could have rolled it up? No even a real giant except if he was the biggest of all…”) were magical enough to complete his unspoken joy at being alive in this world.

Kieron Smith, boy movingly reclaims the frequently abused childhood-point-of-view in fiction, for authentic realism – there is no condescending ‘Young Adult Fiction’ here, no obscene exploitation of childhood vulnerability for Hollywood dramatics – this is life, and this is language, authentic and still warm in our throats from what seems just like yesterday. Did they not say that if Dublin vanished, you could recreate it from Joyce’s Ulysses? Here a Scottish childhood and thus a large part of Scotland can be known and recreated – forever. What an achievement.

Where to next? Suggest a novel from your country that you would recommend to someone who had not read any of your native literature. Send suggestions to info [at] productmagazine [dot] co [dot] uk