Alistair Braidwood salutes Michel Faber’s ambitious take on how music affects us at the deepest level

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

Michel Faber’s Listen: On Music, Sound and Us is a music book unlike many, if any, others, closer to Steven Pinker’s examinations on language and linguistics than about who or what you should be listening to, or a list of essential albums, or tales and anecdotes of rock ‘n’ roll excess. It’s about how we perceive music, and do so in a number of ways – a sensual relationship that is about much more than simply sound. An examination of what music does to us and the complex, and numerous, reasons why. The music we listen to doesn’t change once it has been recorded, but we do, and how we listen also changes.

There’s an early chapter on those who don’t like music, who suffer, if that’s the right word, from ‘musical anhedonia’, meaning that music doesn’t provoke any emotion. To those of us who have musical obsessive tendencies this is unthinkable. I have only met one person who said in all seriousness they don’t like any music, in fact they “just don’t get it”. That was about 35 years ago and my shock at this statement has never left me. Faber goes into closely researched detail as to the numerous reasons that can be the case. Originally I thought this chapter was an outlier, but it sets up the rest of Listen as, if we are to ask why music doesn’t provoke an emotional response in some, we also have to ask questions about why it does in the rest of us, which Faber goes on to do in detail.

It’s not about nostalgia – something the writer claims not to understand, or at least personally experience. To better comprehend it he looks at the phenomenon of YouTube below-the-line comments, which can be viewed as poignant or pathetic depending on your point of view or mood. The comedian Adam Buxton has mined this area for great comic effect, but if you want to find out for yourself simply look at the comments for any video for a popular song from the ’80s, ’90s, or ’00s and you’ll likely find statements bemoaning the fact that people are no longer young, the world is a much worse place than when they were, and music has never been so good since. It’s perhaps the most depressing, yet arguably honest, example of the arrested development that can accompany nostalgia. It’s not about the here and now, but yearning for a past which most likely never existed, and the never-ageing soundtrack to it.

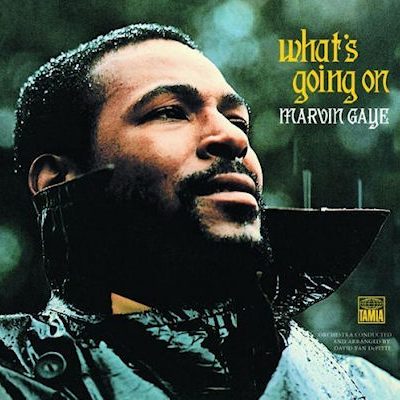

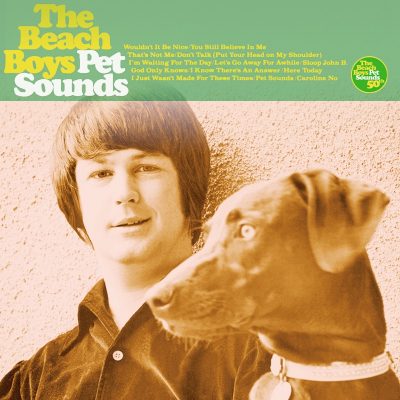

Faber also looks at the apparent desire for absolutes when it comes to music, turning it into some form of competition, one with a league table. Many music lovers desire a definitive answer to the question ‘What’s the Greatest Album of All Time?’ which, for what seemed like decades, appeared to be a two-horse race between Abbey Road and Pet Sounds (Faber remembers Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as holding the top spot in his youth). A quick look at the most recent Rolling Stone Top 500 Albums finds them at numbers 2 and 3 respectively, with Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On at number 1 showing that the more things change, in terms of such lists, the more they stay if not exactly the same then very familiar.

Linked to the above is that nebulous notion of taste, and the desire that others think you have it. We all have taste, but why do we care (if we do) that others share it, or at least approve of it? Can you admit in company that you’ve never heard Marvin Gaye’s magnum opus, or that you prefer Now That’s What I Call Music! 3 over Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue? Of course these things shouldn’t matter, but if they don’t why do they seem to? Faber admits to being one of those people who will peruse the record collections of people he visits, and I admit I do similar, and though I think both of us would claim this is more about curiosity rather than criticism, is that completely true?

Listen also examines the value put on the physical objects which carry music – vinyl, CDs, cassettes and all the other various methods of delivery which have come and gone, and sometimes come again, over the years. What is the comfort to be had in collecting? The need to have precious shelf space taken up with hard copies, some of which will barely have been listened to. Faber offers us the stat – if you like a stat you won’t be disappointed with Listen – that ‘the average album is played 1.2 times’. If you think how often you listen to your favourites, that means some are getting a few tracks played at most. Our treasured collections are destined to become landfill, yet to many of us they hold meaning more than musical appreciation and mere memory, they are linked to personal identity. Faber admits that at home he has a room ‘wholly given over to music’. In that admission there is heady mixture of pride and shame, and much of Listen deals with such dichotomies – a constant pull between the passions and reason.

There is far too much in Listen: On Music, Sound and Us to go into full detail here. It also looks at the problems of structural racism, misogyny, and xenophobia in music and much of the discussion around it; the hegemony of western white men, and increasingly dead white men, continuing to dominate – what the writer calls ‘the same old canons of white noise’. The chapter on ‘foreign’ pop is not only informative it is, as with the book in general, incredibly entertaining and will send you spiralling into a musical rabbit hole to learn more. Faber says ‘it’s not the aim of this book to make you own more stuff’. In that, I fear he may have failed.

There are also investigations into fashion, fandom, tribal allegiances (examining why people who profess to be individuals often align themselves with groups who all look and like the same) and if music can ever be fully separated from those who make it, what many now refer to as ‘the Morrissey conundrum’ though the book offers other examples. Faber also considers the effect music has on young, and even unborn, children through to what happens not when the music dies, but when those who listen to it do. A comprehensive inquiry from cradle to grave.

For those of us who know Michel Faber as a writer of great novels, including Under The Skin, The Book of Strange New Things and The Crimson Petal and the White, Listen: On Music, Sound and Us may be surprising in content, but not in style. Faber’s playfulness, unusual thought process, and exquisite use of language are all present and correct. While Listen is a personal love letter to music – Faber admits it’s his first love – it’s a book for every curious music lover who wants to understand a little better why they like what they like, and why we are who we are.

Listen: On Music, Sound and Us is published by Canongate