Isabelle Stroud salutes the comic creators fashioning a new wave of female characters

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

“Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man twice its natural size” – Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, 1929.

Comics and graphic novels have rarely been seen as a serious subject, accorded the same level of analysis and praise as highbrow literature and the ‘formal’ arts. However, since their rise in the 1940s, comic book pages have reflected society’s shifting and often conflicting ideologies about women and gender roles. To the young child picking up a fresh issue of Detective Comics, the towering and muscular superheroes within were mesmerising – imprinting on their young minds an affirming vision of mainstream masculinity. For others, comics were a counteractive expression of resistance – endorsing the feminist, gay rights and environmentalism movements of the later sixties and seventies. Comics are and always have been an effective societal litmus test.

With this in mind, I visited London’s October Comic Con convention – one of the largest celebrations of all things pop culture. As I walked through the enormous warehouse, a colourful kaleidoscope of brilliant characters jumped out from the stalls. Among these was a larger-than-life Black Widow and Wonder Woman – created to be powerful, patriotic symbols but likewise to cater singularly to the male gaze. Wonder Woman’s curvy hypersexual figure is purposeful, with her creators in 1941 specifically requiring her to be ‘scantily clad’.

Every corridor of stalls I wandered down was plastered with posters of these blatantly objectified fantastical female bodies. Kelly Sue DeConnick, feminist icon and creator of Captain Marvel, once quipped that most female comic characters could be easily swapped for a ‘sexy lamp.’ The truth of that still stings, even in 2025. Indeed, the disappointing lack of fictional stories truly centring women was summed up in 1985 by Alison Bechdel. Her strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, would serve as a platform for the famed ‘Bechdel Test’. Here, a film would ‘pass’ if it had at least two female characters that talked to each other about anything other than a man. At the time, the sheer number of cinematic features that failed this low bar made her point effectively.

Although there has been improvement, the mainstream comic book industry still falls into relegating women to plot devices and ‘sexy lamps’. Market dominators Marvel, DC and Image do little to alter this poor performance. Notably, in April 2024 female writer and artist credits on Marvel issues numbered a mere 11.5%.

More incriminating is the statistic that only 34% of DC women are considered ‘bad’ or villainous characters, in contrast to over 50% of men. Although it is difficult to judge how sophisticated these ‘good’ characters are, the imbalance suggests that female characters are mostly relegated to roles of conformity and passivity. As one exhibit on misogyny in modern comic books noted, the ‘damsel in distress’ trope has a sticky permanence even in the twenty-first century.

However, if the aim is to create female characters with real nuance and complexity, Comic Con also offered a wealth of examples that succeeded.

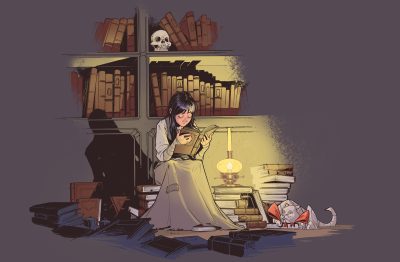

One hidden gem at the convention, Porcelain: A Gothic Fairy Tale, is a perfect example of how female characters can be thoughtfully conceptualised. This fantasy debut by Benjamin Read and Chris Wildgoose features a protagonist, Child, who was ‘never intended to be conventionally pretty,’ instead characterised by a round, expressive face often animated with fiery resilience. For Wildgoose, it was important that his female characters be ‘grounded,’ ‘scrappy,’ and ‘dependable,’ allowing them to feel three-dimensional and whole.

One of the most surprising encounters was with Matthew Hardy, co-writer of a War of The Worlds spin-off series Thunder Child. Despite their decision to add female leads to Thunder Child, they expected their sci-fi audience to be overwhelmingly male. In fact, a broad proportion of their visitors at the convention were women. Certainly, this is encouraging – showing that female characters, writers and consumers are breaking into genres typically associated singularly with men. Indeed, Thunder Child’s female Captain is a powerful force throughout the comic, becoming a resilient and highly visible protagonist.

Above and Below: The powerful Captain in Matthew Hardy and Rob Jone’s Thunder Child: Issue One. A notable example of a strong female character in a Sci-Fi comic – this issue is well worth a read.

Images: Thunder Child: Issue One, Mad Robot Comics.

As such, the most admirable element of the convention was its diversity. Comic Con assembles a rich representation of what the pop culture world has to offer – synthesising both the outdated and the new. Although the ‘sexy lamp’ characters of the past retain a visible presence, they are only one element in a sea of brilliant new artwork and ideas. You don’t have to look far to find excellent female representation in a growing number of genres.

Above and Main Image, top right: The thoughtfully imagined Child in Benjamin Read and Chris Wildgoose’s Porcelain: A Gothic Fairy Tale.

Images: Porcelain: A Gothic Fairy Tale, Improper Books.